We know how to fix peer review (Part 2)

There is no top down system better than the existing system. The next step requires shifting to bottom up, emergent systems.

In “We know how to fix peer review” I pointed to the problems that exist with peer review, which everyone agrees on. I then described the solution that seems obvious to me, and many others, but not everyone understood it. The reaction from that group was, “if you have a better system, tell us what it is! We’d totally use it! But I don’t see you describing a better system here”

This is confusing because, I did describe it! But I see the problem now: the people saying this are waiting for a top-down solution. They see the rules currently in place for how we decide on truth via a central authority, and they ask, “what is a better set of rules?”. But that’s not what we’re describing. We’ve reached the limit of what is possible with top down systems. What I’m pitching is: no central authority.

What if things get worse without a central authority?

This is totally possible. But I think the things we are most afraid of are already happening, and will continue to get worse. It feels counter intuitive, but we’re holding tightly onto the feeling of control, and safety, and that is ITSELF what is putting us in danger & making things worse.

The transition from central authority to decentralized is difficult, and potentially dangerous. But I think necessary, and possible to pull it off with minimal risk as long as:

Everyone understands the end goal, and can work independently towards it

Everyone understands the risks, and can pull their brakes when they see danger

Note that while I’m talking specifically about peer review in this series, everything about this problem applies to all of our centralized systems. If we manage to transition peer review, we can apply the same template to everything else1.

What’s the worst that can happen?

If there is no central authority that stamps a piece of research as “certified truth”, then it’s possible for misleading & manipulative things to spread & grow in power. Imagine a youtuber or some blogger who declares scientific institutions as corrupt, says that he has access to the real truth, and starts telling people what to do & what to think. This is obviously dangerous, if that person is spreading things that are not true/harmful.

But, ideally, if the central authority stamping things as truth was good at its job, this wouldn’t even be a risk at all. Ideally people can see WHY the thing is true, and don’t just take it on faith. Ideally, if the central authority makes a mistake, people can (1) notice it and (2) correct it. So, someone else spreading things that aren’t true should fail to spread2.

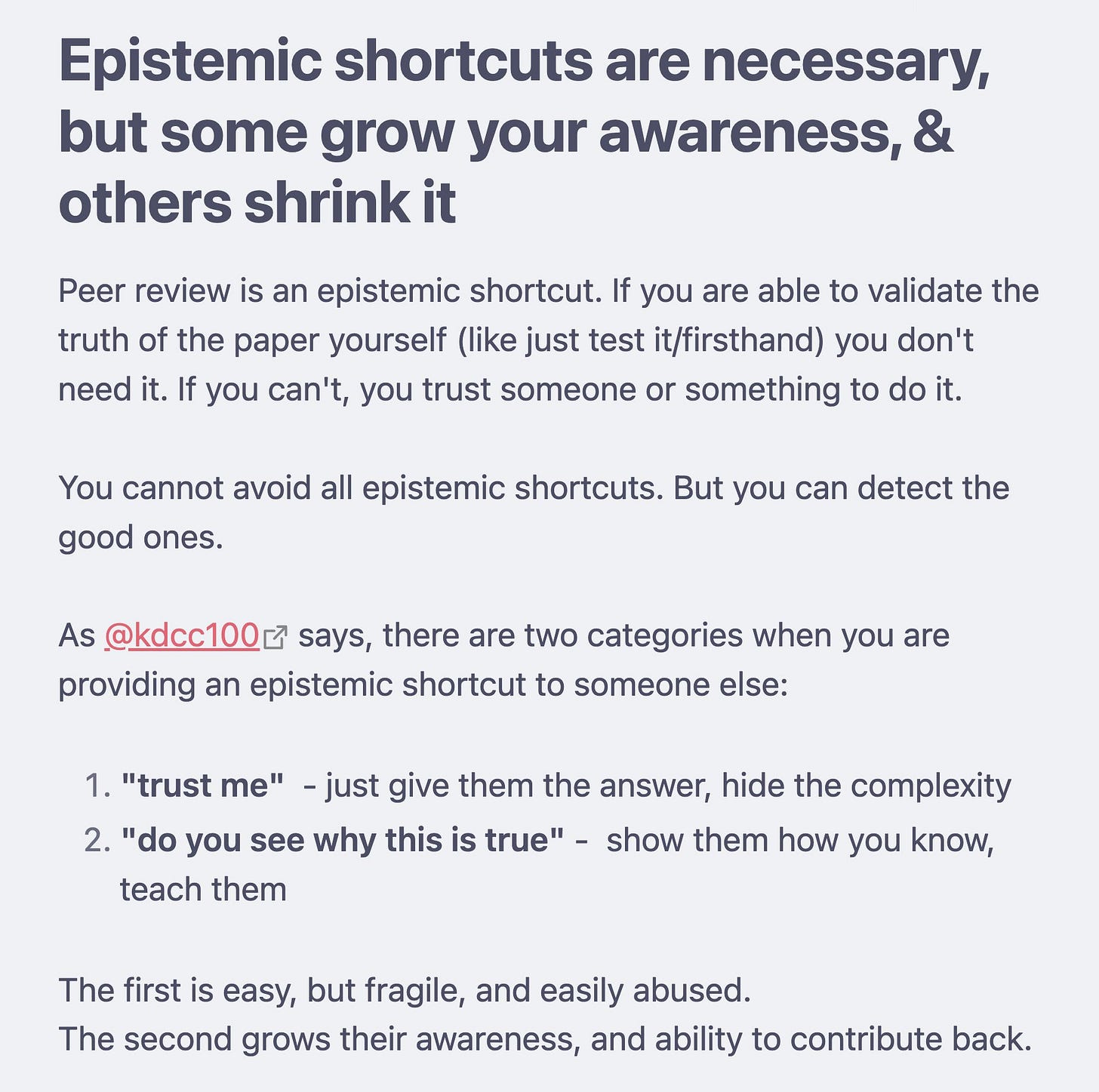

In other words, trust in authority is an “epistemic shortcut”, which is not inherently a bad thing. It’s bad only if it shrinks people’s ability to discern truth.

What should you do as a producer of science?

In the current top-down system, you submit your work to a journal.

In the bottom-up system, you understand the purpose of the work you’re doing: the knowledge you produce is most useful if it reaches the people who are looking for it. Those people may be the average citizen, it may be a professional in industry, it may be a political group. There MAY exist a pipeline for your work to reach those people, or there may not. If there isn’t one, you need to solve that problem too.

You are not just a cog in a machine, blind to how your piece connects to the big picture. If you are producing valuable work, but it’s not going anywhere, if there is a bottleneck, you look at that bottleneck and shift to try solving it3.

A much better system for the creation, propagation, and consumption of scientific knowledge is already evolving, and it will accelerate the more people recognize it and choose to participate in it. Anyone who sees bottlenecks in the system, and tries to solve it is rewarded. The meta process of: the work of solving bottlenecks being invisible/not rewarded is ITSELF a bottleneck that people are working on.

Some properties of this newly evolving system:

Peer review happens openly, on social media/GitHub. Anyone can participate. You take what is useful to improve your work. Giving out feedback is rewarded because it doubles as curation/teaching/science communication

No gatekeeping, the best ideas come from anywhere. Tenured professors regularly exchange feedback with anonymous internet users. It’s all about whether you have the skill & knowledge to contribute or not

Science communication is NOT just something done for the layperson. It is part of the core lifecycle of science. Scientists themselves need someone doing the work of finding what is good, true & useful, and surfacing it

Paradigms openly compete. There is no “one true paradigm”

The last point is huge and hasn’t really happened yet, but I think it’s the next big phase. “Is Water H2O?” a history/philosophy of science book articulates this really well, that if we find two conflicting paradigms, we could just pursue both of them. We don’t have to argue about “the right one”. If one really is better than the other, it will generate more successful predictions & thus accumulate resources.

This does require that we have a non-zero tolerance for groups of people that think they are doing science & pursuing truth, but clearly are not. You are allowed to look at another paradigm and say “those guys are crazy, their methods will never yield any useful results”, and anyone who invests their time or money is doing so at their own risk.

Ultimately what allows us to decide what is true is what helps us make successful predictions, and that is something that ANYONE can judge. You don’t need to be very smart, or know any of the details of the methods, to know if someone’s predictions came to pass.

Getting peer review fixed first makes sense because we need mechanisms to surface truth & good ideas, and to establish trust, in our pursuit of fixing, well, everything else.

In programing terms, I’d think of this as “no need to make a hard-coded exception for the central authority”. You want a system that elevates truth, and that if the central authority itself fails to spread truth, then the system should adapt around that.

This is similar to how employees across large corporations coordinate: ideally every employee understands how their work contributes to the bottom line/the stock price, and if they notice that they’re not helping, they try to work on something different, or tell their manager etc. This is an “emergent” bottom up system because it orients around an outcome, not a process.

Reading this, my immediate thought is that learning good epistemics (so that you can understand what is good research and what isn't) is a difficult skill that requires commitment and effort. And people who don't already have a good grasp on it will have a hard time realizing it.

BUT we have a social mechanism to solve for this called school. Young people, who we invest in. And a simple prerequisite is to have highschool and college classes simply being about reviewing scientific articles and figuring out if they are trustworthy or not and why.

Reading through 5-6 science papers hyper critically and developing a taste for what is good and bad science does not feel like something that is above %50 of college graduates. and that would be a game changer.

Thank you for your very logical look at decision making. It reminded me of something I learned about Einstein, he always reevaluated a scientific hypothesis several times in the desire to really make a decision on what was the undeniable truth.

When he discovered the final equation that was the absolute true answer it seemed to scream out in his brain and sensibilities. We must trust our instincts in finding our truths.