The Human Memome Project

Half science, half performance art

The Human Genome project was an international scientific project to map humanity’s geneome. It took 13 years, across labs from 18 countries.

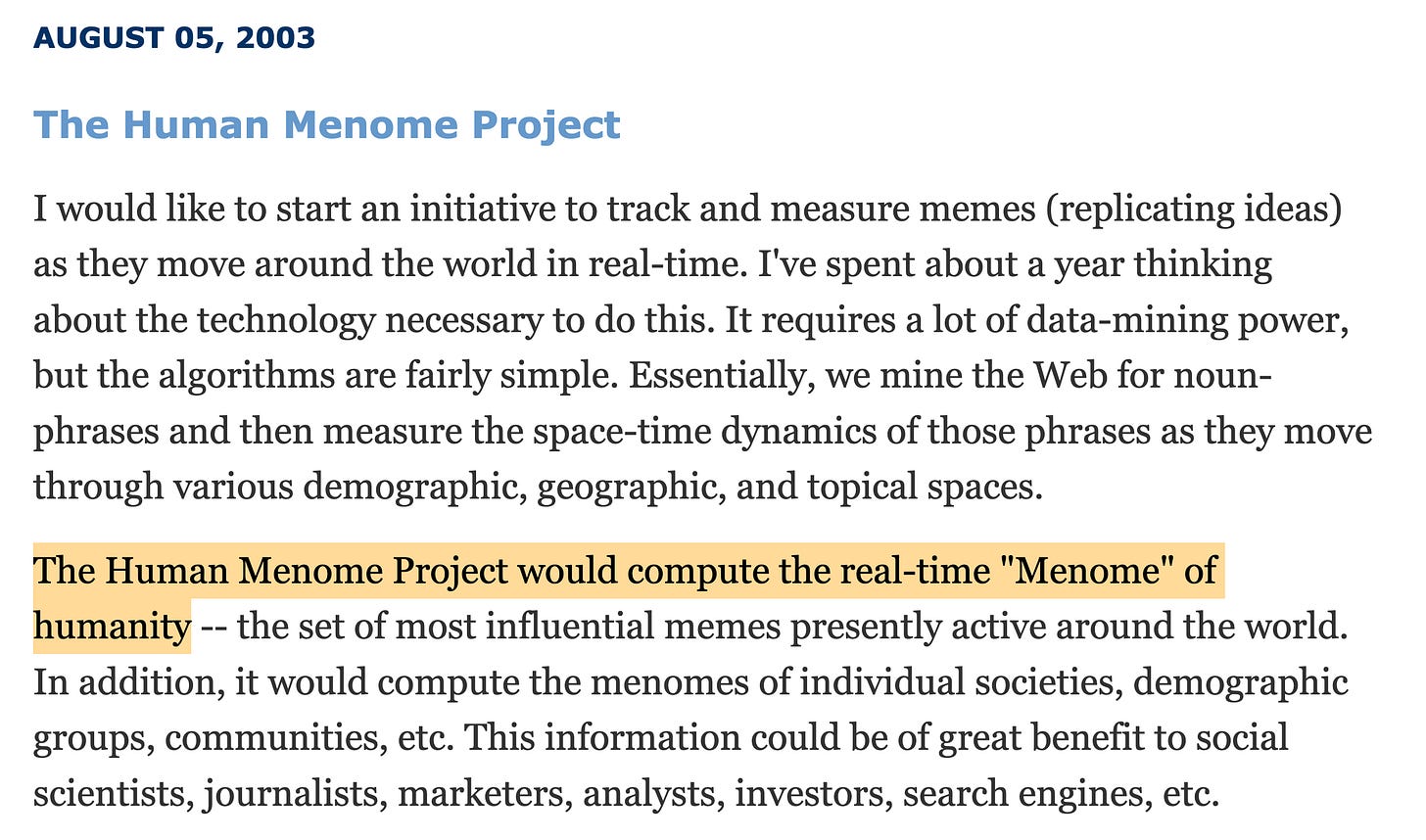

The Human Memome project is a civilization-wide effort to map our own beliefs, how they reproduce & evolve, and the functional effects they have on our behavior1.

Unlike genes, there is no objective, neutral way to observe the ideas in people’s minds & their evolution. This project is impossible to pull off without reshaping human civilization. But this is a feature, not a bug: it has the potential to steer the collectives who participate. Towards the best possible future, and away from collapse.

Who gets to steer humanity? It’s the same answer to: “which cell in the human body gets to steer it?” - it’s all of them, all of us, as Cody Hergenroeder puts it:

One of the earliest references I could find to the Human Memome Project is this 2003 blog post by Minding the Future:

I’ve been thinking about this project for over a year now. I don’t really know where to start explaining it. I decided it’d be most fun to walk you through how I started to think about it.

Who Are We Now?

In March 2024 I heard about the book, “Who Are We Now” by Blaise Aguera on Steve Levitt’s podcast. Blaise worked on AI & LLMs at Google, but on the podcast he was talking about “spaceship earth” and humanity as a superorganism.

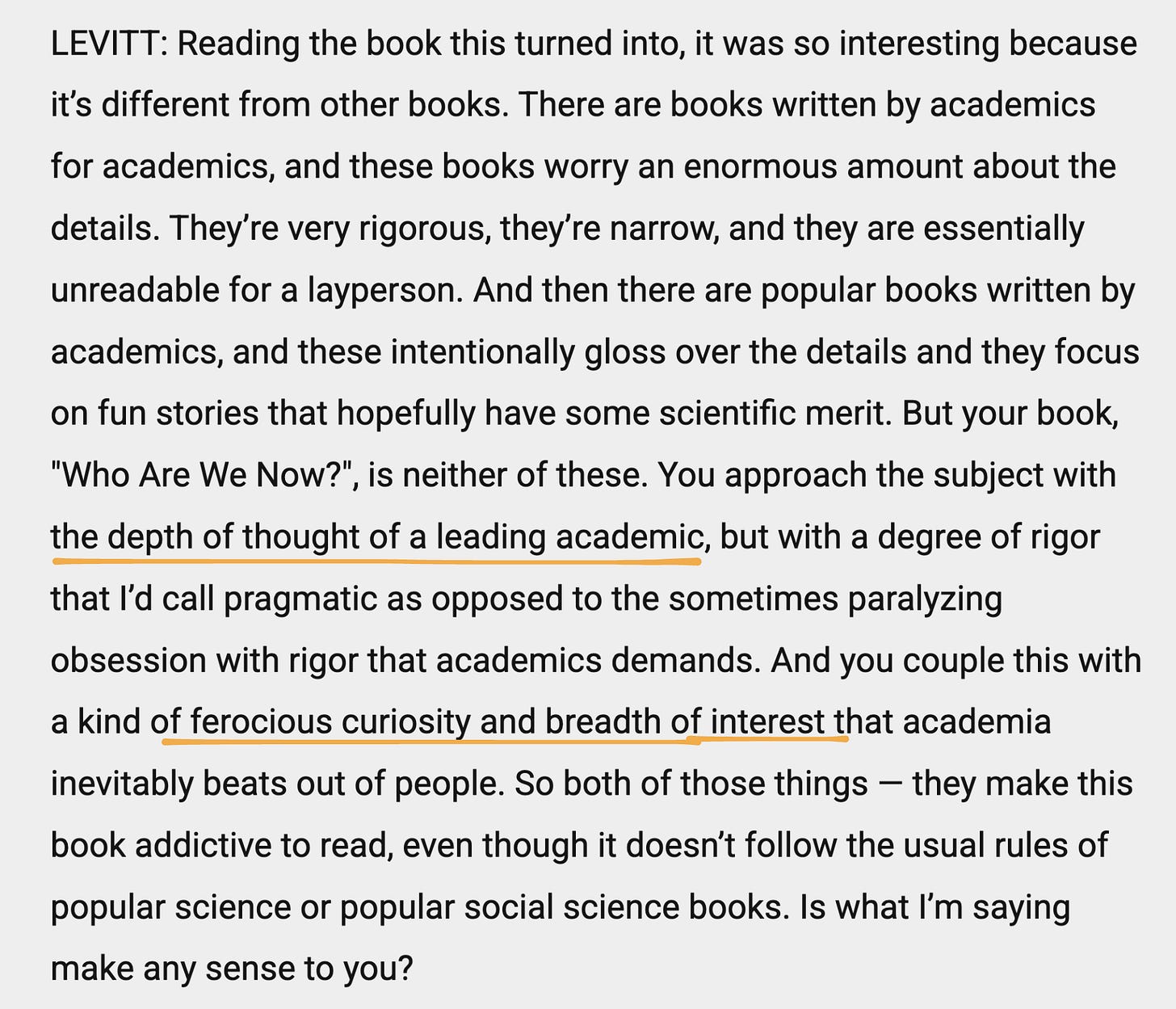

Steve says what struck him about the book is that it does two things that are seemingly contradictory:

explains things with the depth of a leading academic

it’s fully accessible to the layperson, and infused with joy & curiosity

I’ve always felt a kinship with people who see art & science not as separate things2, so I immediately bought it. I now consider this the first “open memetics” textbook, despite him never actually using those words. What he set out to do was paint a picture of humanity. He did this by surveying people, over 6 years, through Amazon Mechanical Turk. He did this not as an academic, nor as part of his job, but just as a side thing. For fun.

Did you know you can just do that, by the way? You don’t need permission from a university, or a company, or the government. If you want data on, say, what people over 50, who live in Texas, and who are not home owners, think about anything, we have infrastructure that anyone can use that lets you reach them3.

The book paints a beautiful picture of humanity, which is extra beautiful BECAUSE it’s true. He doesn’t shy away from explaining the ugly parts. Some people think you have to hide the ugly parts, otherwise people “won’t get it” or will take away the wrong message. Some people think the average person is stupid, that you have to dumb things down4. But not Blaise. He’s not talking down to you here. He’s giving you a fighting chance to understand something on the frontier of *his* knowledge, like a peer throwing down a ladder. After that it’s up to you, if you wish to climb5.

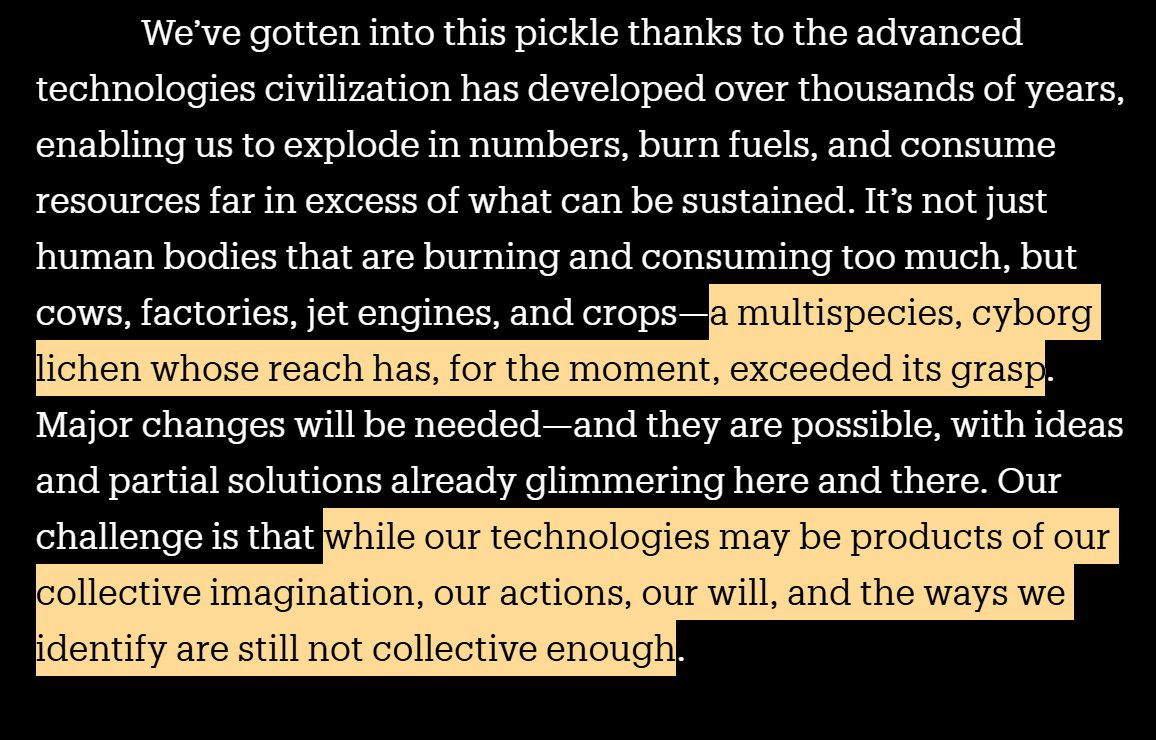

There’s one line in there that has lingered in my mind ever since I read it, about the current state of humanity:

We are a multispecies, cyborg lichen whose reach has, for the moment, exceeded its grasp.

Do you see it? This precarious moment we’re in today6? A species so large and powerful that its reach can reshape the surface of the planet, but its *grasp* is lagging behind, able to touch, but unable to steer. Not yet.

I’ve never gotten a chance to ask him this, but I wonder what Blaise’s goal was in writing this book. I wonder if he was attempting to nudge culture, by writing a book about how culture changes, and the possible directions it could go. I wonder if that’s why he spent so much care making it beautiful AND accessible AND rigorous. I wonder if that’s why he made a version of the book completely free, so it would spread further. I wonder if he wanted to inspire others to pick up where he left off, to start doing open culture study, writing about it, and involving others. So that we may start shaping our culture together. Like one big game. One big theater performance.

I can tell that Blaise knows how ideology shapes how people think, that it defines the range of thoughts our minds can reach for7. He starts the first chapter talking about something uncontroversial, about how a question as simple as “are you right handed or left handed?”:

can have an “excluded middle”, people who are neither this nor that, or who are both, or something completely different

can be very difficult to answer, because (1) there are different definitions of those things for different people, AND (2) those definitions change over time

but DESPITE all that complexity, we CAN find truth, empirically. He shows you how, step by step. It’s not easy, but it’s not beyond your ability, dear reader

In the US, left wing spaces tend to be more comfortable with this kind of fuzziness of truth, but struggle to be decisive or make judgements. Right wing spaces tend to have much clearer boundaries about what is good or bad, beautiful or ugly, but do so by erasing a lot of complexity. Blaise reconciles both8 of these modes:

For a data nerd like me, there’s something reassuring about visualizations like these. Yes, language is fuzzy, almost everything is a “spectrum,” and “reality,” whatever that means, is hard to pin down. However, the data reveal a strong underlying degree of agreement about what people mean when they talk about their own handedness. Put another way: handedness is real.

An essential feature of the way language is used to mark out and constantly renegotiate the way we all think about things. Without that give and take, language couldn’t evolve.

(from chapter 2: https://whoarewenow.net/chapter-02/)

Just because it’s fuzzy doesn’t mean you can’t find truth, make precise statements, and test your predictions. At the same time, we understand that the truth evolves over time, and that we have a hand in shaping it.

Why doesn’t an Open Memetics Institute exist?

In a previous life I worked as a software engineer. In one of those jobs I had access to an A/B testing dashboard. We used it in very benign ways: before shipping a feature to your billion active users, you pick a random group of 1 or 2 million, give half of them the new feature, and observe them over a week or two. If their behavior moved in a negative direction (people bought less stuff, or spent less time on the app), you wouldn’t ship the feature.

I started to wonder why we weren’t using tools like this as part of scientific research. Inspired by Blaise’s book, I ran to my friend, a sociology PhD student at Cornell, to tell him about my big idea. Like, could I contribute to science by making a web app that goes viral & collects data?

The answer was no. You can’t do that because you need informed consent. You can’t just launch a viral social experiment on the human population for science.

This was the first time I understood the “open-closed research gap”: you can run a live experiment on a billion human beings & watch their behavior, as long as you don’t tell anyone about it.

Obviously, this is really dumb. It doesn’t have to be this way. If academic institutions couldn’t launch these experiments9, and big tech companies didn’t want to, then maybe there could be something in the middle that could do this.

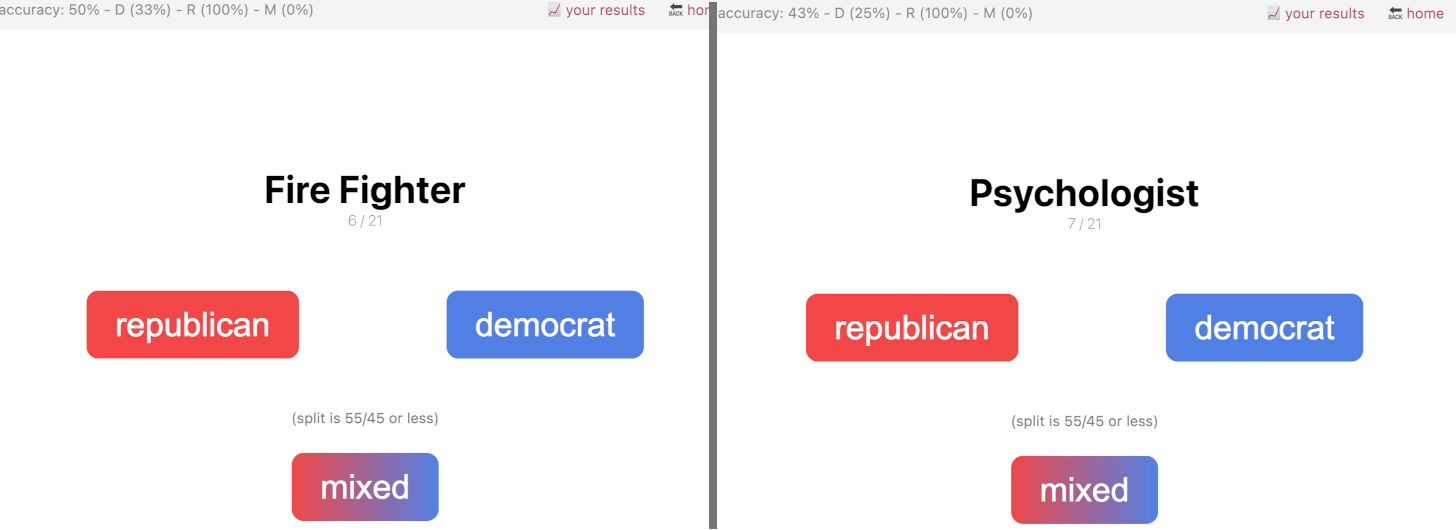

I made a prototype for this called “Shape of America”, a quiz game that tests people’s perception of how polarized America is, and all the data collected is publicly available in real-time.

I never “officially” launched this because I noticed the source data I was using was a few years old. I managed to get fresh data from FEC records but never got around to updating it, and it felt like “the moment had passed”. But I think this is a great template.

What I love most is that by playing this game, you get something out of it AND contribute to society at the same time. You learn something (either confirmation your model is accurate, OR a chance to find your blindspots & fix them), AND contribute to this dataset, painting a portrait of how society perceives itself.

The other beautiful thing about this is that it doesn’t matter if it reaches a representative sample of the US population. When Aella does her cultural surveys, people often say “this is biased! not representative!” but that’s a bogus criticism. If I have a warped perception of political polarization in the US, and so does everyone in my network, it does NOT matter what the aggregate public thinks. The GSS is the largest sociological survey in the US, but it does not represent *me* and my reality. The patterns of my subculture may too small to show up in the aggregate scale.

I envision a world where I publish the results of my studies, centered around my IRL network, and my online audience, then someone like Noah Smith or Adam Mastroianni or Hank Green clicks “fork” and runs a version of that same study with their audience. Do the results reproduce, or are they wildly different? The fact that the game is kind of competitive creates an incentive for it spread. Like, does your audience have a more accurate model of reality than mine10? We can playfully one up each other while mapping our shared, evolving beliefs, & spreading truth.

This is how a scientific study can “go viral”, bottom up. If I run the study, and the results look crazy, it may be that we’ve found something novel, or just that my network is really weird in this specific way. If you run the study as well and the pattern persists, then it brings more attention to the study, others repro, and on and on.

The most important thing to realize here is this: surfacing information in culture is NOT separate from changing it. Taking the test about your perception of the world, CHANGES your perception of the world, especially when you see how you compare to everyone around you. Again, this is a feature, not a bug. This is a mechanism for steering culture. We SHOULD be biased in what truths we want to surface.

There does not exist a neutral culture scientist. This is why it is very important that the Human Memome project be decentralized, and bottom up. There cannot be one canonical “Open Memetics Institute”. Each culture must have their own, almost like ambassadors. There has to be at least one person or group in the culture memetically aware enough to understand in what way these experiments are shaping their people11.

How do we start?

I’m not sure yet.

I’ve been thinking a lot about collecting “one of each”. Having one representative from each culture12. It’s much easier to understand what’s going on in Israel / Palestine for example, when you’re friends with both a jewish family and an Arab family. You can then “zoom in” and find the Arabs that are pro-Israel, and the Israeli people who are pro Palestine. You can paint the picture of the world that each side sees, and that then allows you to predict how each group will interpet the same information in very different ways.

Imagine a GitHub repo13 that just documents “what is true about the world, from the prespective of <ideology/subculture>”.

Let’s say a version of this exists, and you see a page on “what liberals think about Trump” or whatever. Now, if you are yourself a liberal, or have liberal friends, you can tell for yourself whether this writeup is accurate. If it’s NOT accurate, it tells you one of two things:

Whoever wrote it has poor theory of mind of liberals, OR has no liberal friends

*You* are not as representative of “liberals” as you thought! There exists a schism in our culture that you are not aware of!

You either gain knowledge about the author’s “picture of the world”, and what is missing from it (and, if you want to, you can contribute a fix), or you gain knowledge about the culture being written about.

One thing that this exercise will demonstrate is that these “collective minds” / cultures often have very poor theory of mind of each other, *as a function of* their connectivity. People often hate those that they know nothing about. But this is a hard message to spread because, SOMETIMES people do already know a lot about those they hate.

But my point is, in ALL cases, it’s useful to learn about “the enemy”. Either you realize you were wrong, and they actually want the same things you do, OR you realize they are *exactly* as evil as you expected, in which case, having more accurate models of their reality helps you beat them, outcompete them, or convert them to your side.

This is how I think we can turn “culture war” into “culture science”. I think the first ideology/culture that starts playing this game, studying themselves, and others, will very quickly (1) grow immune to a lot of propaganda, and coordinate amongst themselves (2) be more effective at spreading their ideology. This will create a pressure for other cultures to use the same tools, in order to compete, or they will begin to shrink / try to close up & limit connectivity.

I picked the words “civilization-wide” carefully here. The scope of beliefs we care about are “the ones that have an effect on us”. This includes two broad categories: the “inner” ones of your own tribe, and the “outer” ones of the tribes you interact with. If there are people you cannot reach, and they don’t want to interact with you, then they are fully out of scope. Symmetric awareness is the ideal (either both aware, or both unaware). We focus on “persistent beliefs” and “the functional effects they have” as a way to prioritize the vast search space. We’re NOT doing a taxonomy of all the things people believe, we’re looking at what things shape our reality. If it has no observable effect, we don’t have to worry about it.

I used to tell people the reason I got into computer graphics was because it was the only field I was aware of whose academic conferences came with a trailer for their technical papers. It’s highly technical, AND beautiful.

I dream of a world where the ad infrastructure that we’ve created is co-opted to do something beautiful and useful. I wrote a story about this called “The best ad I've seen all week”

Feynman said “the whole idea that the average person is unintelligent is a very dangerous idea” because it leads to a downward spiral in society. I wrote about this in Feynman’s Razor. Basically: how can you tell when you’ve dumbed down an idea too much? It’s when someone who is capable of understanding the idea can’t tell what you’re talking about it.

normality captures this really well in “You are not only allowed to use your brain when editing Wikipedia, it's your job”. Some systems try to dumb down/simplify to meet the user where they’re at, which is a kind of downward spiral, while others try to lift up, and give them enough scaffolding to realistically do that. You can’t make people grow, but you CAN remove all obstacles to their growth.

The idea that civilization hangs on a precipice is a kind of infohazard. How to handle infohazards safely will be a very important puzzle to solve in the Human Memome project, which is necessarily fully open & participatory. One answer is to use legibility as a filter: you can speak about things in a way that only those who already know it will understand it. Another mechanism you can use is blasphemy & stigma. Some truths are ugly, and people are more reluctant to believe them. This natural force is a feature, not a bug in our work.

This is what I was trying to explain in “Suppression of Truth is Necessary for the Best Possible World” but I think I put off too many people by saying “suppression”. It’s not about trying to actively stop people from finding the truth. It’s more that, by default, ideas aren’t legible. If you’re going to put time & effort into making it legible, you want to prioritize things that are good & useful.

In modern times, we call a package of beliefs that constrains your range of thought an ideology. In ancient times, they called it a religion. The relationship between memetics & religion will come up again and again. An important insight here is that all human minds have some “package of beliefs”, some fundamental axioms that you hold. It’s not a question of whether you subscribe to one or not, only a question of which one (this includes the option of a homegrown one). This is why I no longer think of religion as something you can opt out of, it’s merely a question of whether you intentionally chose your package of beliefs, or if it chose you. The belief that “everything has a scientific/rational explanation” is an example of an unfalsifiable religious/axiomatic belief.

I think this theme of “reconciling both” will come up again & again in the Human Memome project. Right or left, capitalism or communism, art or science, left brain or right brain, rational or intuitive, all these things SEEM like they’re in conflict, and they can be if you see them as two ends of a single axis. But we will discover in what ways they are not. This is a core theme in David Rug’s “How Collective DreamWeaving Can Heal the World”. As far as I can tell, he’s basically describing the necessary infrastructure for the Human Memome project, and how he expects it to alter society if it succeeds.

This “open-closed” gap that a few months ago University of Zurich launched a secret social engineering experiment on a subreddit, to great backlash. Their justification was “people are doing this all the time in secret, & the open research community is too far behind, we need to catch up”. I wrote about this here.

A common theme in a lot of these open memetics science experiments is that they double as marketing, which is how I think we will “fund” a lot of this work. If your audience does really well on a test like this, it’s something you can brag about.

Traditionally, this is the role of priests.

Where to draw the boundaries around “a culture” is a fuzzy but empirical question. One way to define it is via “shared attention”. A group of humans forms a “collective mind” if they pay attention to the same things, and respond the same way, and their shared language evolves together.

If you’re not a programmer, think of a “GitHub repo” as a google doc that anyone can edit, but edits have to be approved by the author. If the author won’t approve your edit, you can make a copy of the doc, and anyone can see all copies that have been made.

I just skimmed Chapter 18 of "Who Are We Now" - lots of B's! I was pleasantly surprised.

Then I skipped around Chapters 20 & 21 - less alignment. It seems like he took a lot of care to examine psychology/sociology... but then the claims about "consider these technological marvels of the futuuuure!" is unsubstantiated, leaves unaddressed most of the fairly easily-graspable reasons why the agro-industrial-digital system can’t possibly have a future

The reason readers might let his (not evil, just dumb) oversight slide is:

1. He gives a bit of lip service to some threats

2. He uses language of the natural scientists and hippies (superorganism, mycelium, Gaia - I assume that's where you pulled the terms from) and quotes some prominent experts from those fields

3. He just spent a whole book telling you all these true, well-explained, mind-blowing things about yourself, so you're prone to give him a pass on the ending (“the hamsters are so cool and well-understood = their cage will keep functioning; it must!”)

… And his stance on invasive species makes me think he's never seen a Japanese honeysuckle thicket with his own eyes

Reading books from different authors for the same period of history is very fun because I get a sneak in how people lived, thought and how that lead to what we have here. This sounds so exciting, also I finally pieced together your open memetic project. It is very cool :))